Love it or hate it, bots are settling in.

You can see them popping up everywhere, automating work and replacing humans as AI enthusiasm seems boundless in many quarters. And no doubt, some aspects of life are in the crosshairs. The arts has been one of the first, with artists complaining about being steamrolled. From Hollywood’s writers and actors to social-media influencers, musicians, and illustrators—everyone’s got a horror scenario about the bleak and soulless world of AI-generated culture.

Some of them have pretty strong feelings about it. Both fear and loathing. Actors and writers held strikes. Artists and authors want compensation when their work is fed into the learning machines. I’m not sure where we’re at in the AI hype cycle, but Silicon Valley is giddy with its new toy. Eggs, omelettes and all that.

What are artists complaining about? You probably know already. Matthew Inman at The Oatmeal fears the machine will take work from human craftsmen. Like the Luddites before him–he would like to smash it all down. He rails against the pervasiveness of the tech, feeling that no human endeavor will be untouched as moneyed corporations and government go all-in. Next, he sees AI tools as enabling mediocrity, allowing the midwit to punch above his weight, like a kid pretending he’s making music by pressing the demo button on a Casio keyboard. He laments that the side effect of fast tracking and outsourcing the creative process will be loss of growth and joy for makers. Downstream, consumers who’ve embraced the mediocrity or mistaken it for excellence, are being denied the benefits of great art. But as with most of these protests, it’s not clear who he’s angry with—the people who use AI, the people who build it, or the fact that such technology exists at all. Probably all of the above.

Humanity has always had a complicated relationship with its tools. Socrates worried that writing would ruin human memory. Medieval clergy opposed mechanical clocks for placing human artifice on God’s times and seasons. Critics of the printing press warned of “a confusing and harmful abundance of books.” Anglican minister Edmund Massey, perhaps the earliest of vaccines skeptics, preached against small pox inoculations in 1722. He condemned the new practice as playing God, since he viewed illness as a divinely-appointed form of judgment. Historically, new things were usually greeted with suspicion. These days, we care a little less about what God thinks of our technological innovations, but the rise of artificial intelligence has triggered lots of chatter.

But humanity adapts and on it goes, right?

Technology has always arrived with a promise. The earliest tools were extensions of human ability: a hoe for longer reach; a pot for carrying more water than hands. This tech was basic enhancement, aimed at survival. By the industrial and electrical ages, we had survival fairly well in hand. Technology began promising ease from life’s harsher limits—efficiency, economy, speed. Home appliances promised more comfort, less toil. Automobiles and airplanes promised to outrun time and distance. Medicine promised to fend off pain and death. The digital age has gone further still. These tools aren’t aimed at easing the burden of being human—they promise escape from it altogether.

It’s not uncommon to meet the assumption that technology is neutral, that anything can be used for good or ill. For example, a couch is just a couch. But it could be used to entertain guests or hurled at an enemy, I guess. Yet every invention reshapes more than is intended and each in its own way. A couch might change how you lay out your living room, but a smart phone can keep you up at night, ruin friendships or get you into debt.

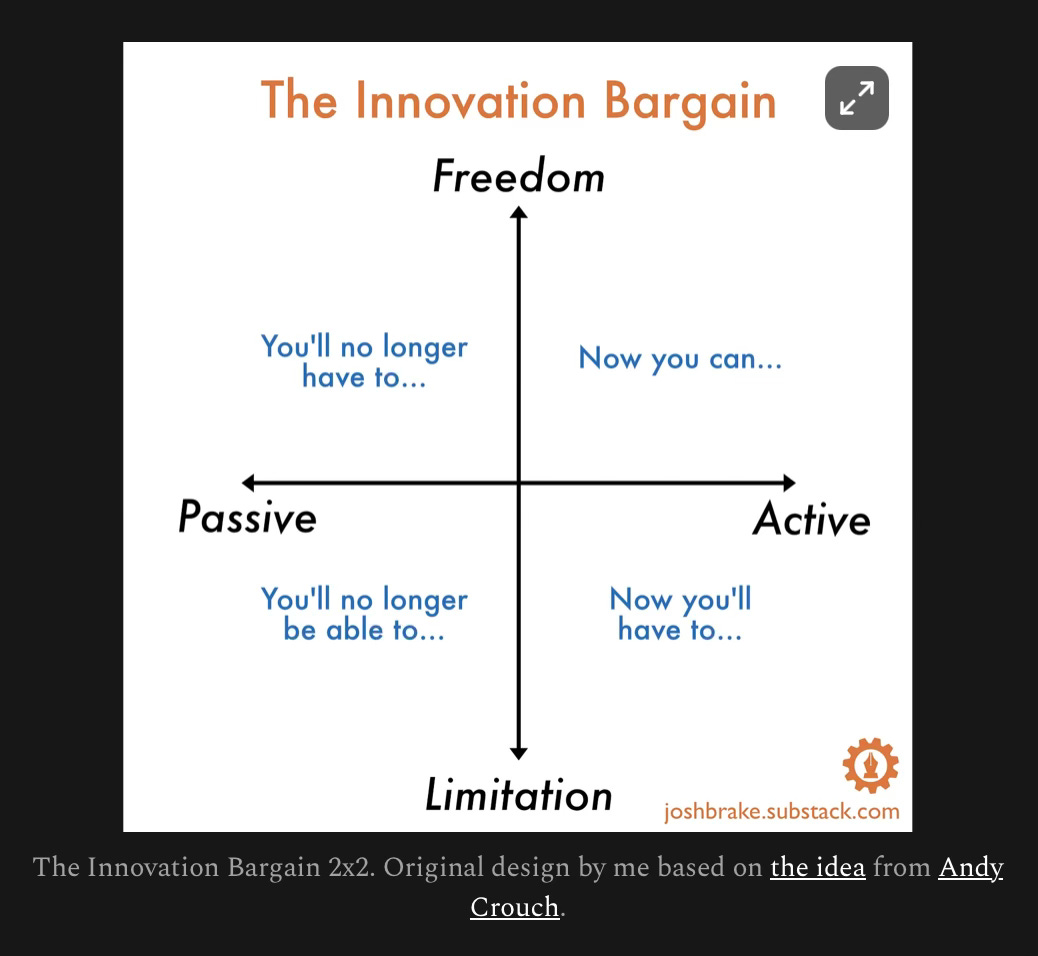

Professor Josh Brake tells of upgrading his road bike to an electric one—what it gave him, what it quietly took away. Every new tool promises speed, ease, safety, control—but as he says “every innovation is a bargain.” We usually ask what our tools can do for us and rarely what they’re doing to us. It’s hard to quantify the affect while you’re in the thick of the cultural smog. Only when it lifts do we notice what’s changed.

Lately, I’ve tried to think through the thought-terminating claim of tech neutrality. Maybe a handy rubric for judging is to think about when tech is philanthropic and when it leans transhumanist—tools can serve creaturely life or they can attempt to undermine it. There’s room to argue about the categories (by all means, have at it in the comments), but some of our newest technologies tip easily into modifying human essentials. We are thinking, learning, suffering, working, embodied creatures, created by God. Every new tool changes how we live, but the question is whether it still helps us live as humans.

Don’t mistake my wariness for rejection. Technology itself is a fruit of human creativity—part of our God-given mandate to shape and steward the world. But since the Fall, our inventions carry both purpose and pride. No tool is neutral, because every tool teaches its user something about power and dependence. The question isn’t whether we should use technology, but whether it helps us live as redeemed creatures—or seduces us into forgetting that we are creatures at all.

The labor-saving devices of yesteryear promised to provide more leisure time than we would know what to do with. Clearly, mid-century inventors never envisioned “notification syndrome” or the existential dread wrought by a forgotten password. Nor the grind of daily commutes, the paralysis of choice and the tyranny of measurement and credentialing. Professor Michael Sacasas once wrote, “When machine-like consistency, efficiency, speed, or production is demanded of creatures, then creatures are made to live as if they were machines.” Not sons motivated by imitating their Father who is working, but for the maintaining of systems and money.

Could we lose our ability to think, as Jeffrey Tucker warns at The Epoch Times? “A student or a worker who relies on AI to generate all answers will not ever develop intuition, judgment, or even intelligence.” The epistemological work of “learning how to learn” might be the most vital skill for the next generation.

Even suffering—the part of human existence that technology most frequently promises to erase—is a uniquely human part of life, this side of Eden. The technocratic mindset sees any discomfort as unnecessary. And so, in the name of compassion, we invent drugs to kill the unwanted unborn and contraptions to suicide the sufferers. Yet, it is suffering that keeps us dependent on our Creator.

I probably don’t need to rehearse the impact of digital connectivity on human interaction. Humans are embodied, made for presence — to look one another in the eye, to share bread, to work side by side, to bury and be buried. Yet our technology keeps pulling us toward abstraction: conversations without bodies, compassion without proximity, outrage without action. We can know what’s happening on the other side of the world while ignoring the person in the next room. All sorts of tools have muted the significance of our physical existence, but digital technologies have made what we stand to lose a little more obvious.

Some inventions do honor our creatureliness; they don’t hinder our ability to live as beings created by God’s—worshiping, judging, working, loving. They amplify the human vocation to steward creation. Others, though, aim at divinity itself. The first kind of tech keeps us human. The second kind tries to make us gods. Like those building the tower of Babel, the goal is to “dissolve the distinction between heaven and earth, mortal and immortal, the transcendent and the mundane.” These are the technologies that promise omniscience, omnipresence, omnipotence, or eternal life—the godlike attributes humanity has always lusted after.

Today we have the full gamut of opinion about our AI future and Christians would be wise to be thinking clearly. At one end there are those, like Sam Altman, who place all their faith in the machines, speaking glowingly of an unimaginably prosperous future where virtual everything is normal and the virtually impossible is a snap. Yet, he is so oblivious to the wrench in a machine future: humans. When he sat down with Tucker Carlson, he seemed genuinely puzzled that morality can’t be averaged out or coded in. Someone will always have to rule on what is good. Meanwhile, outflanking him in fervor are the cheerful apocalyptics who reason consistent with a survival-of-the-fittest worldview: if a superior intelligence rises up and wipes out humanity, then so be it.

And then there are those who have no time for AI devotees and want to claw back some humanity. They aren’t curmudgeons, just sad and concerned. As a self-professed “AI hater”, Anthony Moser has a grim take, warning that those who build AI are slaves and enslaving:

In a kind of nihilistic symmetry, their dream of the perfect slave machine drains the life of those who use it as well as those who turn the gears. What is life but what we choose, who we know, what we experience? Incoherent empty men want to sell me the chance to stop reading and writing and thinking, to stop caring for my kids or talking to my parents, to stop choosing what I do or knowing why I do it. Blissful ignorance and total isolation, warm in the womb of the algorithm, nourished by hungry machines.

Back in 2016 Hayao Miyazaki of Studio Ghibli said of AI content: “I would never wish to incorporate this technology into my work at all..I strongly feel that this is an insult to life itself.” He mourns humanity’s loss of faith “in ourselves.”

But do either of these men have an answer besides a gritty, no-AI Amish-style hold out? Or a nihilist’s despair as the machines rise and rise? They want to convince the ones with the Casio keyboard that there is more. But those guys are probably busy pushing the demo button, over and over. Moser concedes that those who are satisfied with AI-generated content probably won’t hear such arguments: “If you’re pushing slop or eating it, you wouldn’t read it anyway. You’d ask a bot for a summary and forget what it told you, then proceed with your day, unchanged by words you did not read and ideas you did not consider.”

I’m not anti-technology; to live in this world is to use it, but we need not be used up by it, as Moser fears. Technology started by helping humans do things they couldn’t do, but now we need to guard the things only a human can do. There will be some who treat AI like the airplane: they don’t know how to build it or fly it or how it works, but will happily just get in and go where it’s going. We need some who will not check their brain (or faith) at the login screen.

The slow march of progress is easy to trace along the threads of what is called progress. From swords to guns to drones; from hunting to farming to printing food; from heralds to letters to phones to neural links. Vulcanized rubber to pneumatic tires to jet engines and space ships. Extension to ease to escape. Every leap promises liberation but brings tripwires. Our newest inventions make life faster even as they claim to make it easier. The noise multiplies while discernment withers. Move slow and make things is an antithesis to the acceleration, grounded in the Word of eternal life.

Wendell Berry once wrote: “It is easy for me to imagine that the next great division of the world will be between people who wish to live as creatures and people who wish to live as machines.” It’s clear we can’t always trust the makers of tech to have creatureliness in mind. They think about improvement, money, power, progress and throwing off constraint. We consider stewardship, worship, redemption and eternity. There are those who don’t recognize they are creatures, those who can’t stand to be one. Distance, pain, dependence, mortality—all the things that remind us we are creatures—are part of the curse. Believing the machine can save us will result in counterfeit redemption: power without repentance, knowledge without wisdom, presence without love, eternity without God. The only One who ever reversed the curse did it by taking it on His own body—not by code but on the cross.

Other stuff I wrote that you might like:

Thank for writing this, it clarifies so much. It makes me wonder, after your other pieces!