The Numbers Don't Add Up

The myth that right-wing holds a monopoly on violence doesn't stand scrutiny.

There was a brief moment, following the death of Charlie Kirk, when those on the left called for “taking the rhetorical temperature down.” A brief moment—just like when President Trump was shot. But soon enough, the deflecting and blaming ramped back up.

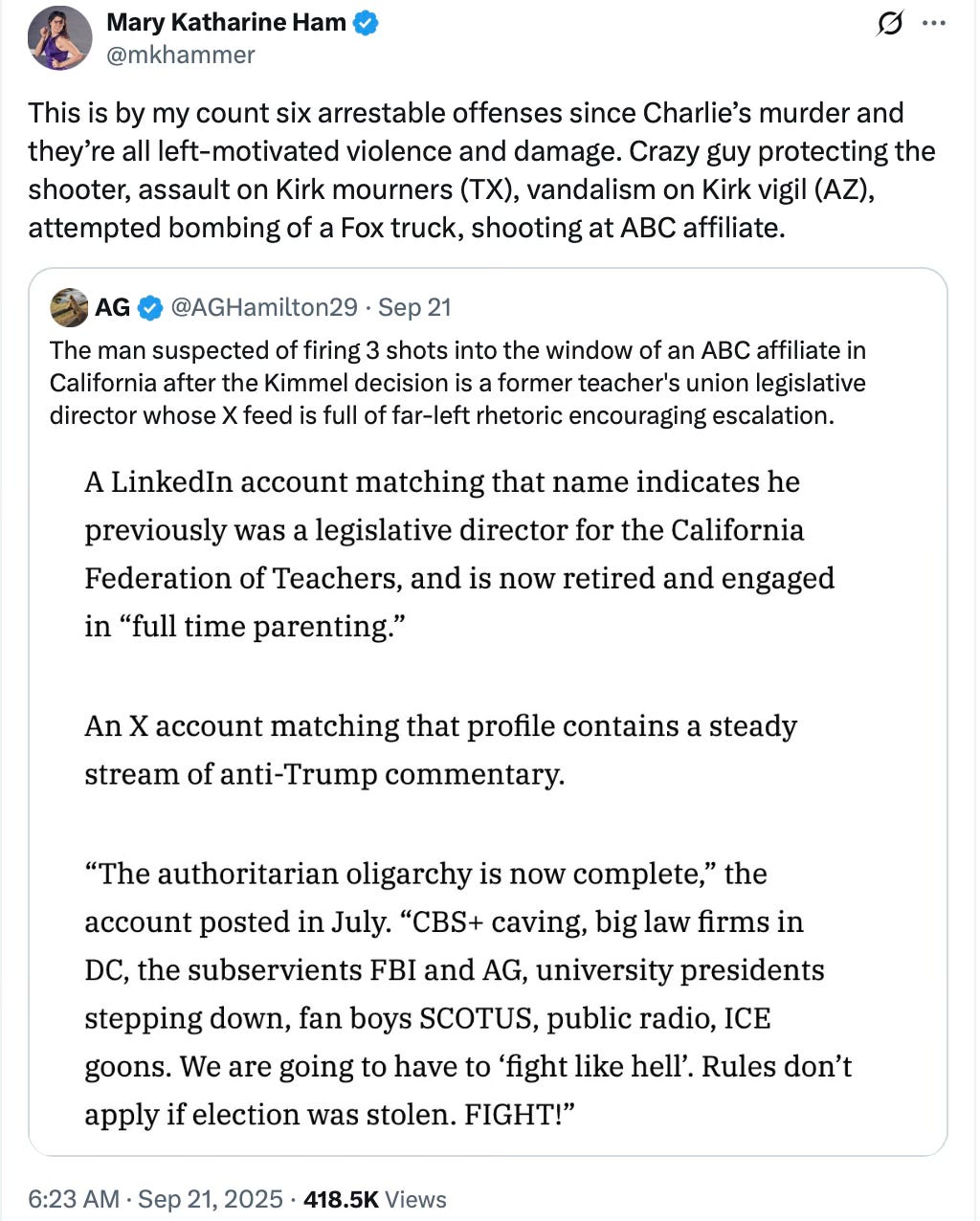

Since Kirk’s death, major violent incidents have piled up. Mary Katherine Hamm listed a number of them in a recent post:

Since then, more have followed:

A 23-year-old man reportedly shouting “Free Palestine” was charged with opening fire at a New Hampshire country club, killing a guest at a wedding being held there.

A young man took his own life after firing shots at an Immigration and Customs building in Texas. He had written “anti-ICE” on his bullets and writing online that he wished to inflict “terror” on agents.

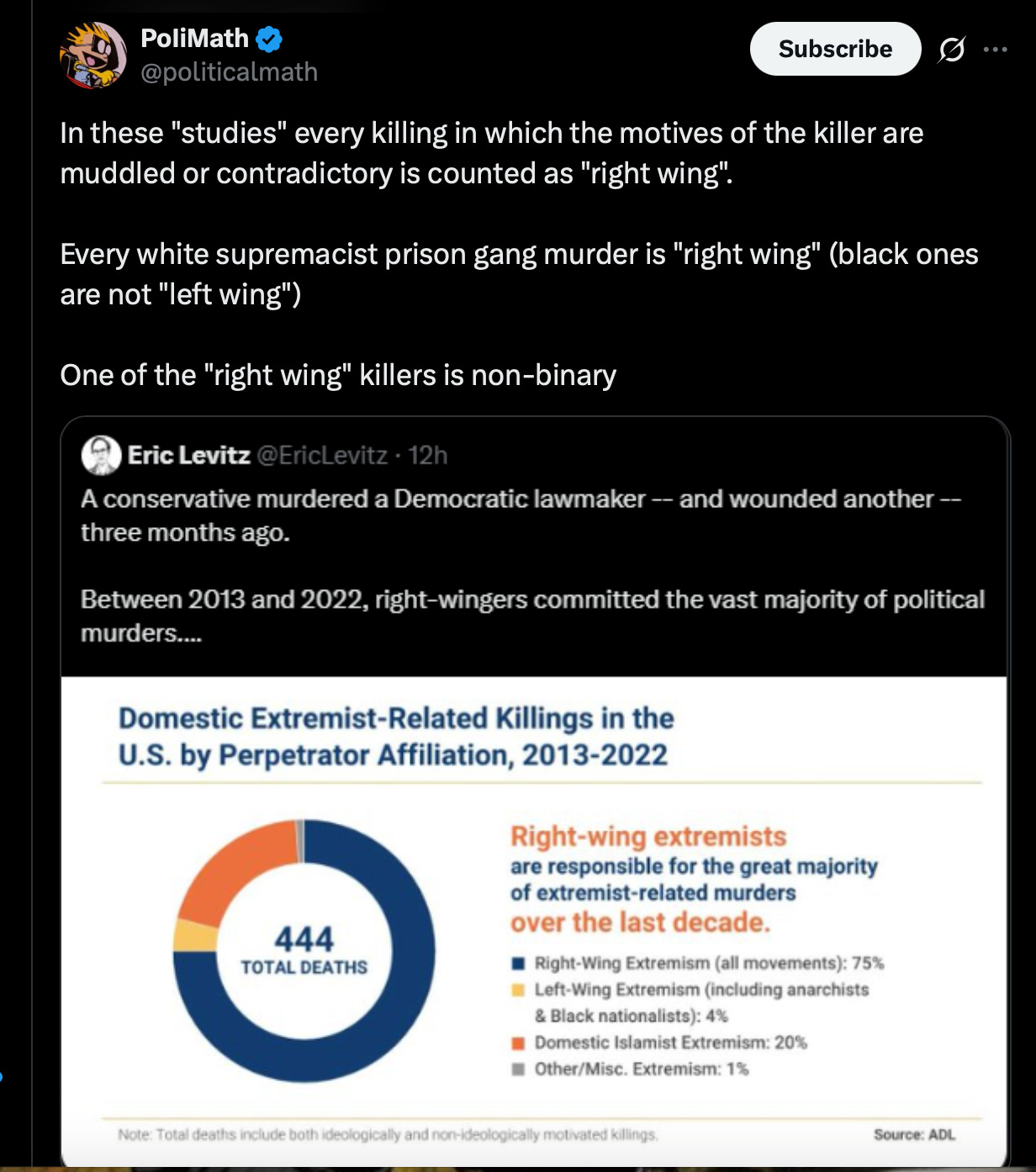

Yet many corporate media outlets continue to insist that we “may never know the motives” behind this violence—and in any case, that the right is responsible for most of it. A version of this chart, showing right-wing violence dominating the landscape, has been widely circulated by the press:

But scrutiny of the data shows otherwise. Writing at the Washington Examiner, Tim Carney pulled apart four of the most-cited studies:

“The four studies cited these days have different methodologies, all of which call into question their accuracy, even-handedness, or relevance to the question of right-wing political violence.”

One study left out violence at BLM protests while including violence recorded at Proud Boy rallies. Islamist anti-Semites were lumped in as “right-wingers” by default.

Amuse went further in parsing the problem:

“One widely cited stream of reports counts every homicide committed by a person with white-supremacist interest, including domestic disputes and intra-gang murders with no political purpose. In the same breath, it excludes left-wing violence that does not produce a corpse… Left-wing attacks that injure, burn, intimidate, and terrorize but that do not result in death are omitted because no one died.”

Perhaps most skewing of all is the habit of inferring ideology from the identity of the victim:

“The method equates theme with motive, and then motive with right-wing identity. Such reasoning would be rejected in any other empirical domain.”

So apart from all the bickering online, why does it matter? Amuse lays out how poor anyalsis trickles down to citizens:

Labeling shapes resource allocation and legal focus. When the data tell the public that right‑wing violence dwarfs left‑wing or Islamist violence, agencies are pressured to divert attention and funds accordingly. That may be wise in some periods. It is reckless if the numbers were built to sell a narrative rather than to inform about risk. It also warps civic understanding. Citizens begin to see ordinary conservatives as adjacent to violent fringe actors. Speech is chilled. Political engagement is stigmatized. The result is a brittle public square in which statistical fog is used to distress one side of the aisle.

Writing in National Review, Charles C. Cooke offered a more philosophical warning:

“It is, however, to distinguish between madness and evil, between chaos and design, between agency and vassalage. We Americans are a self-governing people, and our institutions presuppose our free will. To this order, the madman poses a wholly different threat than the sinner, and, if we are unable to work out which is which, we will become helpless in the face of both tests… A government that can only see one danger is a government that will miss the next danger.”

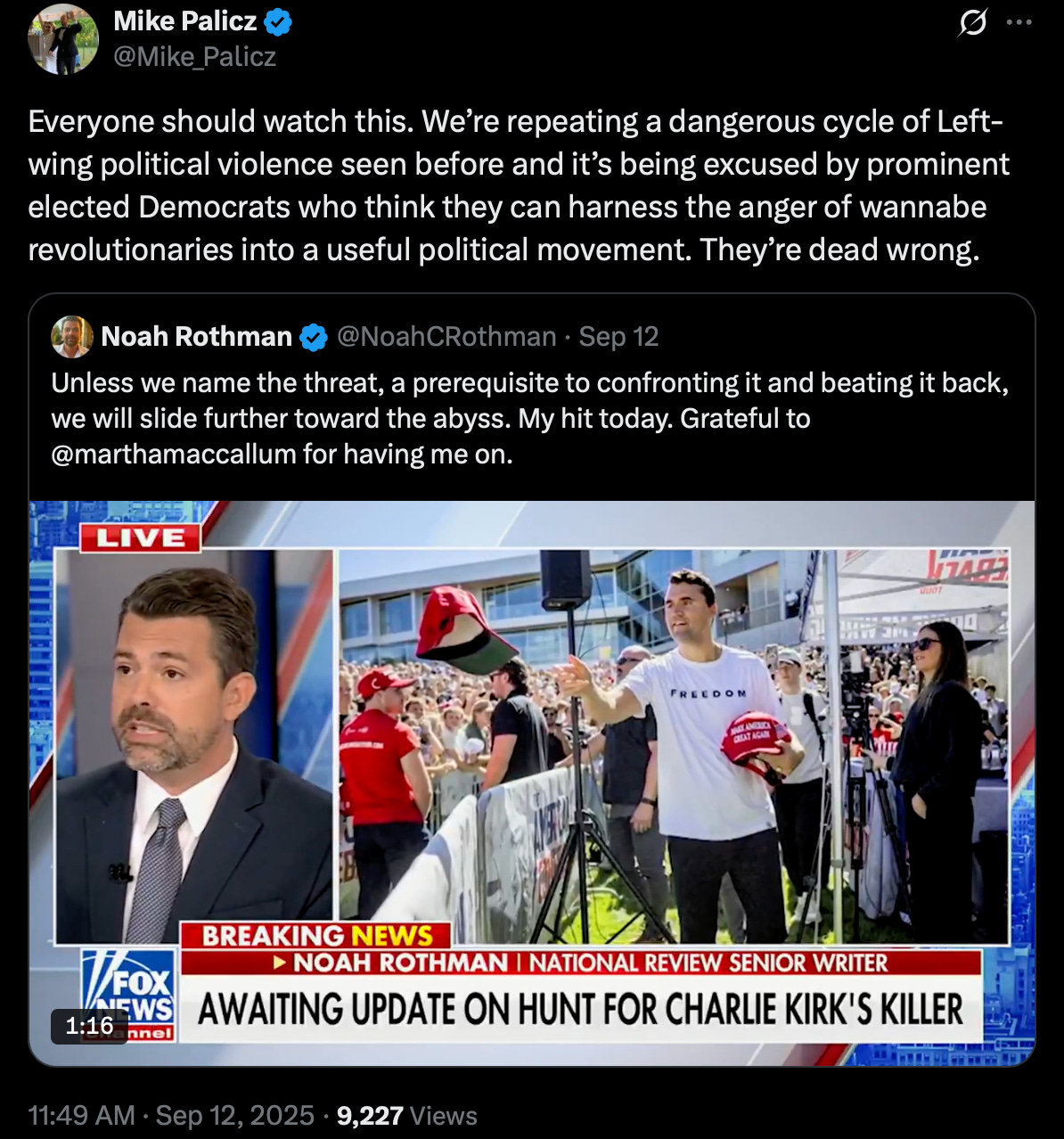

Noah Rothman, who often writes about violence perpetrated in the name of progressive causes, notes that Madison and the other framers were rightly concerned that tribal politics might lead to bloodshed. When people decide America’s institutions can’t deliver the social change they demand, fatalism sets in. That fatalism now fuels a growing number of left-leaning voices who openly say that “political violence will be necessary to save America.”

It makes intuitive sense: if you are convinced that identity politics should be prioritized over family and nation, that systemic racism and poverty are the roots of all evil, and that MAGA really are Nazis, then shocks and terror seem justified. You can shoehorn the facts into your ideology, resulting in blinkered conclusions which suit your position better: “misogyny is the common thread” in shooter manifestos. It’s a secutive delusion. Rothman even argues that the right mostly turns violent when it borrows progressive ideology—when it begins to see people as tribal avatars, dismiss courts as illegitimate, and adopt anti-Western premises. And he’s right. An ideology that prizes godlessness over faith, intervention over self-control, sterility over life, will eventually lash out when it doesn’t get its way.

This is why the new age of “violence is wrong, but you can understand why” is so disturbing. To break the cycle we have to call things what they are. But even more, we must pray for true regeneration of the human heart. Violence is often fomented by a small vanguard, yet the uncertain and the untethered will follow the mob unless they are given examples of people who stand firm. Our task is to be those examples—steadfast in truth, anchored in Christ, unwilling to be swept along by rage.